OVERVIEW

The U.S. stock market edged lower last week by roughly one percent. Only three of the eleven S&P 500 sectors had positive returns. Growth and small-cap stocks dragged the averages down by dropping more than one and a half percent.

International stocks fared no better. About $22 billion flowed out of global stock funds last week, and the AC World ex-US index dropped 1.2 percent. Nearly $2 billion, however, flowed into government bond funds. The 10-year U.S. bond yield fell to 1.69 percent, as returns to long-term Treasury bonds climbed higher. For the most part, investors are still favoring higher-quality, investment-grade bonds to lower-quality, high-yield bonds.

Natural gas and oil dragged commodity indices lower. Gold prices, however, are still up quite substantially for the year. About $3 billion flowed into gold funds last week, despite prices dropping nearly half a percent. The U.S. dollar strengthened further, gaining 0.67 percent.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Framing Expectations – A Long-Term Perspective – Most people, when first starting out on their investment journey, think they already know how their investments are going to perform over the long run. Or, at the very least, they have formed some general expectation. History tends to be a good starting point for establishing these expectations, and history suggests the stock market nearly always goes up in the long run. However, it can be dangerous to assume that stocks will always go up in a straight line and return the average market return, year after year.

Stock prices are volatile (i.e., risky), and it’s this volatility that lays the groundwork for investors to (potentially) reap superior returns for bearing risk. However, risk does not guarantee reward — context matters. Long-term stock valuations, or how much we are willing to pay for the future cash flows of companies, matters a great deal. So does the long-term economic cycle, as corporate profits are tied to the overall growth of the economy. If both of these measures are in less-than-favorable positions, then it makes sense for us to temper our expectations for future, long-term stock returns.

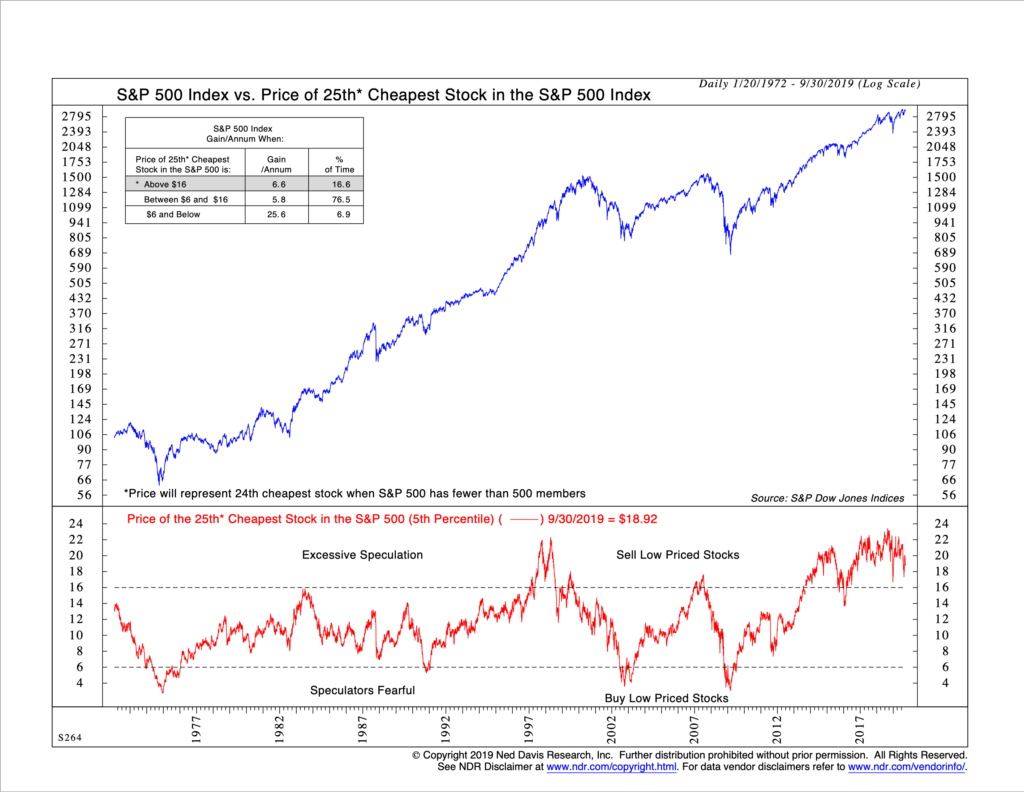

As for valuations, the stock market has appeared overvaluedfor quite some time. Meaning that, compared to historical levels, the price investors are willing to pay for the underlying earnings of companies is quite high. For example, if we take the 25th cheapest stock in the S&P 500 index, investors are currently paying just under $19 for every 1 dollar of earnings that this company generates. Historically, prices above $16 are considered excessive, and returns going forward for the overall market tend to be below average.

I should note that there are many valid and reasonable arguments against using historical levels for valuations, ranging from structural to accounting changes. And by some other measures, which take into account factors like low interest rates and the long-term upwards trend in price-to-earnings ratios, the market is more fairly valued. But, for the most part, we are hard-pressed to find many traditional valuation measures that suggest that the market is undervalued.

For the sake of space and time, I will save the long-term economic cycle discussion for a later date. However, I will say that, by most measures, we are likely in the later stages of the economic cycle. There is undoubtedly more weakness globally than here in the United States. But manufacturing has been in the slumps, and investments in durable or capital goods by companies has been sparse. Nonetheless, financial conditions look solid, and the consumer is still spending (albeit at a slower pace), so the economy appears more or less neutral right now.

When taken together, these yellow flags suggest we should lower our long-term expectations for future stock returns. Excessive valuations and a sluggish economy are powerful forces that can hold back long-term returns. Indeed, the S&P 500 index has only returned a total of just under four percent since mid-2018, when many of these indicators started flashing warnings. So, when the data talks, it’s important to listen.